Thelonious Sphere Monk [1] (October 10, 1917 – February 17, 1982) was an American jazz pianist and composers who is not only considered to be one of the legends in jazz, but "one of the giants of American music".[2]

[]

[]

[]

[]

Monk had a unique improvisational style. He made numerous contributions to the standard jazz repertoire, including "Epistrophy", "'Round Midnight", "Blue Monk", "Straight, No Chaser" and "Well, You Needn't" that are all standards played by professionals and learned, in arrangements of varying complexity, by music students and aspiring musicians.

Monk is the second most recorded jazz composer after Duke Ellington, particularly remarkable in as much as Ellington composed over 1,000 songs, while Monk wrote about 70.[3]

Often regarded as a founder of BeBop, Monk's playing later evolved away from that style. His compositions and improvisations are full of dissonant harmonies and angular melodic twists, and are consistent with Monk's unorthodox approach to the piano, which combined a highly percussive attack with abrupt, dramatic use of silences and hesitations.

Monk at Minton's Playhouse, 09.1947 - William P. Gottlieb

Monk's manner was idiosyncratic. Visually, he was renowned for his distinctive style in suits, hats and sunglasses. He was also noted for the fact that at times, while the other musicians in the band continued playing, he would stop, stand up from the keyboard and dance for a few moments before returning to the piano.

One of his regular dances consisted of continuously turning counterclockwise, which has drawn comparisons to ring-shout or Sufi whirling.

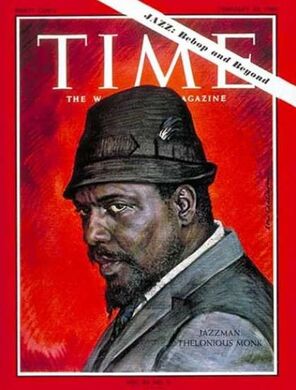

He is one of only five jazz musicians to be featured on the cover of Time Magazine, the other four being Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, Wynton Marsalis, and Dave Brubeck.[4]

Videos[]

Early Life[]

Thelonious Monk was born October 10, 1917 in Rocky Mount, North Carolina, the son of Thelonious and Barbara Monk, two years after his sister Marion. A brother, Thomas, was born in January 1920.[5] In 1922, the family moved to 243 West 63rd Street, in Manhattan, New York City. Monk started playing the piano at the age of six. Although he had some formal training and eavesdropped on his sister's piano lessons, he was largely self-taught.

Monk attended Stuyvesant High School, but did not graduate. He toured with an evangelist in his teens, playing the church organ, and in his late teens he began to find work playing jazz.

In the early to mid 1940s, Monk was the house pianist at Minton's Playhouse, a Manhattan nightclub. Much of Monk's style was developed during his time at Minton's, when he participated in after-hours "cutting competitions" which featured many leading jazz soloists of the time.

The Minton's scene was crucial in the formulation of bebop and it brought Monk into close contact with other leading exponents of the emerging idiom, including Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Christian, Kenny Clarke, Charlie Parker and later, Miles Davis. Monk is believed to be the pianist featured on recordings that Jerry Newman made around 1941 at the club. Monk's style at this time was later described as "hard-swinging," with the addition of runs in the style of Art Tatum. Monk's stated influences included Duke Ellington, James P. Johnson, and other early stride pianists.

Arranger Mary Lou Williams, among others, spoke of Monk's rich inventiveness in this period, and how such invention was vital for musicians since at the time it was common for fellow musicians to incorporate overheard musical ideas into their own works without giving due credit.

"So, the boppers worked out a music that was hard to steal. I'll say this for the `leeches', though: they tried. I've seen them in Minton's busily writing on their shirt cuffs or scribbling on the tablecloth. And even our own guys, I'm afraid, did not give Monk the credit he had coming. Why, they even stole his idea of the beret and bop glasses."[6]

Early recordings (1944–1954)[]

In 1944 Monk made his first studio recordings with the Coleman Hawkins Quartet. Hawkins was among the first prominent jazz musicians to promote Monk, and Monk later returned the favor by inviting Hawkins to join him on the 1957 session with John Coltrane. Monk made his first recordings as leader for Blue Note in 1947 (later anthologised on Genius of Modern Music, Vol. 1) which showcased his talents as a composer of original melodies for improvisation. Monk married Nellie Smith the same year, and in 1949 the couple had a son, T. S. Monk, who is a jazz drummer. A daughter, Barbara (affectionately known as Boo-Boo), was born in 1953.

In August 1951, New York City police searched a parked car occupied by Monk and friend Bud Powell. The police found narcotics in the car, presumed to have belonged to Powell. Monk refused to testify against his friend, so the police confiscated his New York City Cabaret Card. Without the all-important cabaret card he was unable to play in any New York venue where liquor was served, and this severely restricted his ability to perform for several crucial years. Monk spent most of the early and mid-1950s composing, recording, and performing at theaters and out-of-town gigs.

After his cycle of intermittent recording sessions for Blue Note during 1947–1952, he was under contract to Prestige Records for the following two years. With Prestige he cut several under-recognized at the time, but highly significant albums, including collaborations with saxophonist Sonny Rollins and drummers Art Blakey and Max Roach. In 1954, Monk participated in a Christmas Eve session which produced most of the albums Bags' Groove and Miles Davis and the Modern Jazz Giants by Miles Davis.

Davis found Monk's idiosyncratic accompaniment style difficult to improvise over and asked him to lay out (not accompany), which almost brought them to blows. However, in Miles Davis' autobiography Miles, Davis claims that the anger and tension between Monk and himself never took place and that the claims of blows being exchanged were "rumors" and a "misunderstanding".[7]

In 1954, Monk paid his first visit to Europe, performing and recording in Paris. Backstage Mary Lou Williams introduced him to Baroness Pannonica de Koenigswarter ("Nica"), a member of the Rothschild family and a patroness of several New York City jazz musicians. She would become a close friend for the rest of Monk's life, including taking responsibility for him when she and Monk were later charged with marijuana possession.

Riverside Records (1955–1961)[]

At the time of his signing to Riverside Records, Monk was highly regarded by his peers and by some critics, but his records did not sell in significant numbers, and his music was still regarded as too "difficult" for mass-market acceptance.

Indeed, with Monk's consent, Riverside had managed to buy out his previous Prestige contract for a mere $108.24. He willingly recorded two albums of jazz standards as a means of increasing his profile.

The first of these, Thelonious Monk Plays the Music of Duke Ellington, featuring bass innovator Oscar Pettiford and drummer Kenny Clarke, included pieces by Duke Ellington including "Caravan" and "It Don't Mean A Thing (If It Ain't Got That Swing)".

On the 1956 LP Brilliant Corners, Monk recorded his own music. The complex title track, which featured tenor saxophonist Sonny Rollins, was so difficult to play that the final version had to be edited together from multiple takes. The album, however, was largely regarded as the first success for Monk; according to Orrin Keepnews, "It was the first that made a real splash."

After having his cabaret card restored, Monk relaunched his New York career with a landmark six-month residency at the Five Spot Cafe in New York beginning in June 1957, leading a quartet with John Coltrane on tenor saxophone, Wilbur Ware on bass, and Shadow Wilson on drums. Unfortunately little of this group's music was documented due to contractual problems, Coltrane being signed to Prestige at the time.

One short studio session was made for Riverside (only released later by its subsidiary Jazzland in 1961) and a larger group recording featuring Coltrane was split between that album and Monk's Music. An amateur tape from the Five Spot, not from Monk's original residency, but from a later September 1958 reunion with Coltrane sitting in for Johnny Griffin) was issued on Blue Note in 1993; and a recording of the quartet performing at a Carnegie Hall concert on November 29, previously "rumoured to exist",[8] was recorded in high fidelity by Voice of America, rediscovered in the collection of the Library of Congress in 2005 and released by Blue Note.

The Five Spot residency ended Christmas 1957, Coltrane left to rejoin Miles Davis's seminal sextet, and the band was effectively disbanded. Monk did not form another long-term band until June 1958, when he began a second residency at the Five Spot, again with a quartet, this time with Griffin (and later Charlie Rouse) on tenor, Ahmed Abdul-Malik on bass, and Roy Haynes on drums.

On October 15, 1958, the residency having ended and en route to a week-long engagement for the quartet at the Comedy Club in Baltimore, Maryland, Monk and de Koenigswarter were detained by police in Wilmington, Delaware. When Monk refused to answer the policemen's questions or cooperate with them, they beat him with a blackjack.

Though the police were authorized to search the vehicle and found narcotics in suitcases held in the trunk of the Baroness's car, Judge Christie of the Delaware Superior Court ruled that the unlawful detention of the pair, and the beating of Monk, rendered the consent to the search void as given under duress.[9] Monk was represented by Theophilus Nix, the second African-American member of the Delaware Bar Association.

Columbia Records (1962–1970)[]

After extended negotiations, Monk signed in 1962 to Columbia Records, one of the big four American record labels of the day along with RCA Victor, Capitol, and Decca. Monk's relationship with Riverside had soured over disagreements concerning royalty payments and had concluded with a brace of European live albums; he had not recorded a studio album since 5 by Monk by 5 in June 1959.

Working with producer Teo Macero on his debut for the label,[10] the sessions in the first week of November had a stable line-up that had been with him for two years, tenor saxophonist Charlie Rouse (who worked with Monk from 1959 to 1970), bassist John Ore, and drummer Frankie Dunlop. Monk's Dream, his earliest Columbia album, was released in 1963.

Columbia's resources allowed Monk to be promoted more widely than earlier in his career. Monk's Dream would remain the best-selling LP of his lifetime,[11] and on February 28, 1964, Monk appeared on the cover of Time Magazine, being featured in the article, "The Loneliest Monk".[12] He continued to record a number of well-reviewed studio albums, particularly Criss Cross, also from 1963, and Underground, from 1968. But by the Columbia years his compositional output was limited, and only his final Columbia studio record Underground featured a substantial number of new tunes, including his only waltz time piece, "Ugly Beauty".

As had been the case with Riverside, his period with Columbia Records contains many live albums, including Miles and Monk at Newport (1963), Live at the It Club and Live at the Jazz Workshop, both recorded in 1964, the latter not being released until 1982. After the departure of Ore and Dunlop, the remainder of the rhythm section in Monk's quartet during the bulk of his Columbia period was Larry Gales on bass and Ben Riley on drums, both of whom joined in 1964, Along with Rouse, they remained with Monk for over four years, his longest-serving band.

Later Life[]

Monk had disappeared from the scene by the mid-1970s, and made only a small number of appearances during the final decade of his life. His last studio recordings as a leader were made in November 1971 for the English Black Lion label, near the end of a worldwide tour with "The Giants of Jazz," a group which included Dizzy Gillespie, Kai Winding, Sonny Stitt, Al McKibbon and Art Blakey. Bassist Al McKibbon, who had known Monk for over twenty years and played on his final tour in 1971, later said: "On that tour Monk said about two words. I mean literally maybe two words. He didn't say 'Good morning', 'Goodnight', 'What time?' Nothing. Why, I don't know. He sent word back after the tour was over that the reason he couldn't communicate or play was that Art Blakey and I were so ugly."[13] A different side of Monk is revealed in Lewis Porter's biography, John Coltrane: His Life and Music; Coltrane states: "Monk is exactly the opposite of Miles [Davis]: he talks about music all the time, and he wants so much for you to understand that if, by chance, you ask him something, he'll spend hours if necessary to explain it to you."[14]

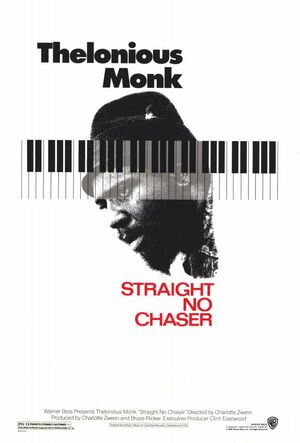

The documentary film Thelonious Monk: Straight, No Chaser (1988) attributes Monk's quirky behaviour to mental illness. In the film, Monk's son, T. S. Monk, says that his father sometimes did not recognize him, and he reports that Monk was hospitalized on several occasions due to an unspecified mental illness that worsened in the late 1960s. No reports or diagnoses were ever publicized, but Monk would often become excited for two or three days, pace for days after that, after which he would withdraw and stop speaking. Physicians recommended electroconvulsive therapy as a treatment option for Monk's illness, but his family would not allow it; Antipsychotics and lithium were prescribed instead.[15][16]

Other theories abound: Leslie Gourse, author of the book Straight, No Chaser: The Life and Genius of Thelonious Monk (1998), reported that at least one of Monk's psychiatrists failed to find evidence of manic depression or schizophrenia. Another physician maintains that Monk was misdiagnosed and prescribed drugs during his hospital stay that may have caused brain damage.[15]

As his health declined, Monk's last six years were spent as a guest in the New Jersey home of his long-standing patron and friend, Baroness Pannonica de Koenigswarter, who had also nursed Charlie Parker during his final illness. Monk didn't play the piano during this time, even though one was present in his room, and he spoke to few visitors. He died of a stroke on February 17, 1982, and was buried in Ferncliff Cemetery in Hartsdale, New York. In 1993, he was posthumously awarded the Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award,[17] and in 2006, Monk was posthumously awarded a Pulitzer Prize Special Citation.[18]

Tributes[]

The number of tributes and homages to Thelonius Monk are too numerous to mention. Some of the more significant highlights:

Gunther Schuller wrote the work "Variants" on a Theme of Thelonious Monk (1960, for 13 instruments) for Monk. It was later performed and recorded by other artists, including Ornette Coleman, Eric Dolphy, and Bill Evans.

In the 2005 film Dave Chappelle's Block Party, drummer Questlove shares the information that of the two songs which Dave Chappelle can play on the piano, one is Monk's "'Round Midnight". Chappelle plays two versions of the song during this revelation.

North Coast Brewing Company has a beer in their lineup named "Brother Thelonious"- a Belgian abbey-style beer (which is likely a nod to Monk's name). The label features a picture of Thelonious Monk in sunglasses and monk's garb. Proceeds from the sale of this beer benefit the Thelonious Monk Institute of Jazz.

Discography[]

See his complete Discography.

References[]

1. ^ http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/389556/Thelonious-Monk

2. ^ Richard Cook and Brian Morton The Penguin Guide to Jazz, 2008, London: Penguin, p1020

3. ^ Giddins, Gary & Scott DeVeaux. Jazz (2009). New York: W.W. Norton & Co, ISBN 978-0-393-06861-0.

4. ^ Time.com

5. ^ Robin D.G. Kelley Thelonious Monk: The Life and Times of an American Original, London: JR Books, 2010, p13

6. ^ http://www.ratical.org/MaryLouWilliams/MMiview1954.html

7. ^ Miles: The Autobiography With Quincy Troupe, 80

8. ^ Chris Sheridan Brilliant Corners: A Bio-Discography, 2001, Wesport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, p80

9. ^ State v. De Koenigswarter, 177 A.2d 344 (Del. Super. 1962).

10. ^ Marmorstein, Gary. The Label The Story of Columbia Records. New York: Thunder's Mouth, 2007, pp. 314-315.

11. ^ Monk, Thelonious. Monk's Dream. Columbia reissue CK 63536, 2002, liner notes, p. 8

12. ^ Gabbard, Krin (1964-02-28). "The Loneliest Monk". Time (Time, Inc.) 83 (9): 207. doi:10.2307/779343. http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,873856,00.html. Retrieved 2007-11-12.

13. ^ Voce, Steve (2005-08-01). "Obituary: Al McKibbon". The Independent (Findarticles.com). http://www.findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_qn4158/is_20050801/ai_n14828122. Retrieved 2007-11-12.

14. ^ Porter, Lewis (1998). John Coltrane: His Life and Music. University of Michigan Press. pp. 109. ISBN 0472101617.

15. ^ a b Gabbard, Krin (Autumn, 1999). "Evidence: Monk as Documentary Subject". Black Music Research Journal (Center for Black Music Research — Columbia College Chicago) 19 (2): 207–225. doi:10.2307/779343. http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0276-3605(199923)19%3A2%3C207%3AEMADS%3E2.0.CO%3B2-L. Retrieved 2007-11-12.

16. ^ Spence, Sean A (1998-10-24). "Thelonious Monk: His Life and Music". British Medical Journal (BMJ Publishing Group) 317 (7166): 1162A. doi:10.2307/779343. PMID 9784478. PMC 1114134. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=1114134. Retrieved 2007-11-12.

17. ^ "GRAMMY.com — Lifetime Achievement Award". Past Recipients. National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences. http://www.grammy.com/Recording_Academy/Awards/Lifetime_Awards/. Retrieved 2007-11-12.

18. ^ "The Pulitzer Prizes". 2006 Special Award. Columbia University. Archived from the original on 2007-10-09. http://web.archive.org/web/20071009204956/http://www.pulitzer.org/year/2006/special-citation/. Retrieved 2007-11-12. "A posthumous Special Citation to American composer Thelonious Monk for a body of distinguished and innovative musical composition that has had a significant and enduring impact on the evolution of jazz."

19. ^ Grammy Hall of Fame

External Links[]

- Thelonious Monk Institute of Jazz

- The Official Thelonious Sphere Monk Website

- Thelonious Monk: The Life and Times of an American Original - Official Website

- Thelonious Monk page in Jazz at Lincoln Center's Nesuhi Ertegun Jazz Hall of Fame

- Thelonious Monk's birth certificate

- The Thelonious Monk Website

- Roundabout Monk: The European Monk Website

- Thelonious Monk at All About Jazz

- IMDb entry for Thelonious Monk: Straight, No Chaser

- CBC.ca Article on 2006 Pulitzer Prize Winners

- Thelonious Monk Multimedia Directory - Kerouac Alley

- Thelonious Monk at Find a Grave